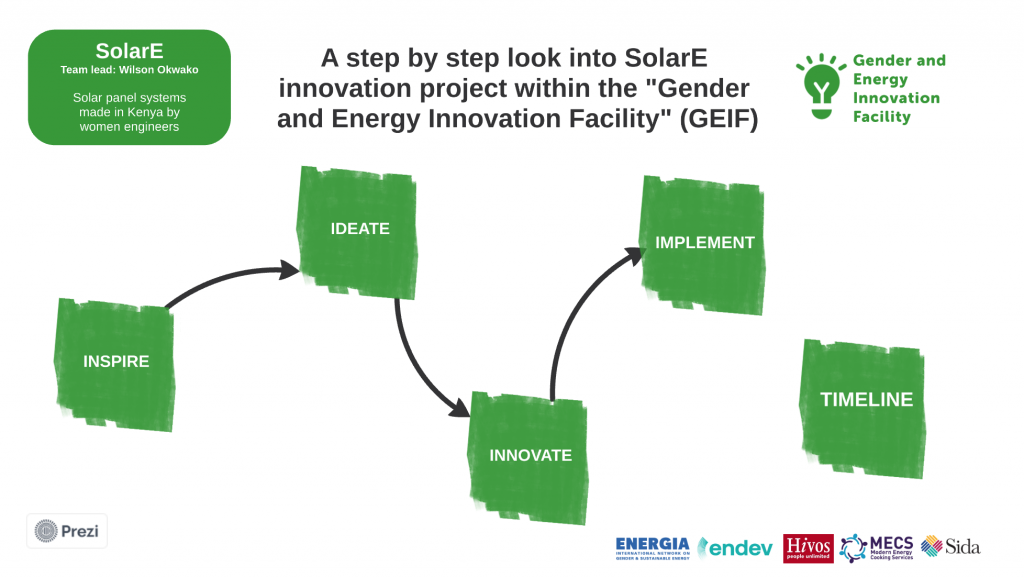

To bridge the gender gaps throughout the energy supply chain and in decision-making groups, ENERGIA, EnDev, Modern Energy Cooking Services (MECS), Hivos and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), launched the “Gender and Energy Innovation Facility” (GEIF) in July 2020. The Facility supports pilot projects in Kenya, Tanzania and Nepal that develop, test and evaluate innovative approaches to address the persistent gender energy challenges.

The Kenyan projects have recently come to an end of their pilot phase, with a mix of interesting findings and promising results that can be reviewed here. In this article, we dive deeper into the experience of one of these projects that stood out for its outstanding commitment to identify and implement innovative solutions that empower women in the energy field.

At the start of 2021, Wilson Okwako started his pilot project as part of the “Gender and Energy Innovation Facility” (GEIF).

As a keen engineer, especially around design and the development of energy-saving technologies, he challenged himself to find a way to locally produce solar systems that would be modular and upgradable, and to source as much as possible in Kenya. This would in turn lead to a more affordable product for locals looking to purchase them.

At the same time, he had a basic understanding of the barriers for women in Kenya to enter this industry as electrical or electronical engineers, and wanted the project to contribute to overcome them, too.

Fast forward to mid-2022, and he has now successfully set up a clean energy production unit under the brand name SolarE. A team of women with a diploma in electrical and electronics engineering have passed the first round of product testing, and are about to scale operations.

Amongst the several projects supported by the GEIF in Kenya, this project stood out for a number of reasons, illustrated hereafter.

Changing gender norms in the sector

Despite the ever-changing situation with COVID19, Wilson stuck to his original plan as best as possible and looked for two qualified women to move the project forward. With the women identified and materials starting to arrive, Wilson was able to rent a small production room in a local building in Kisumu where the training would begin. The idea was to first train two women who in turn would lead their own groups later on.

One of these women completed the training whilst pregnant, then went on maternity leave. Her passion for learning remained, and now she is back and eager to support in training others, sometimes accompanied with her daughter – the youngest to be inspired so far!

As Wilson engaged his female colleagues, he was soon exposed to the situation that women in the sector face. At university they were starved of any practical knowledge, learning everything in theory, but never having the chance of applying this in practice. Furthermore, at that time, women in the sector were poorly underrepresented with only 12 registered female electrical engineers in a database of 17,000 (EBK).

With news of the project starting to spread, more and more women were interested in joining. Wilson and his team set up a WhatsApp group to start providing a central point for these women to meet, discuss the sector and share opportunities.

Initially, the aforementioned two women were part of the train the trainers project, and quickly learnt the skills needed to produce the prototypes. They combined their intellect, attention to detail and previously learnt theoretical knowledge extremely well, and under the guidance of Wilson moved through the production process quickly.

After just under four months of on-the-job training, the original pair of women was now ready to pass on their knowledge to further female participants, and produce the final product, SolarE, that would then be sent off for testing to ensure the product could be sold on the domestic market. The scaling phase, which started upon conclusion of the first project, will continue to recruit women, with a target of 12 women to be employed, trained in various elements such as wiring, soldering, assembly and finally manufacturing of the final product to be sold.

One area where this project stood out is its commitment to the gender element of innovation, and the learning curve Wilson underwent and continues to go through. His passion and motivation are shared by his two female team leads, and the business culture that is apparent seems contagious.

Solving local sourcing issues

Whilst the training and production team took shape, one main issue facing Wilson was around sourcing the materials. He found it difficult to source some materials according to the original budget, due to changes to import taxes. Further to this, delivery times varied depending on where he ordered them from, which made it hard for him to plan the initial training sessions. In addition to the usual logistical issues, COVID19 played its part, disrupting supply chains and making procurement of materials expensive and timely unpredictable.

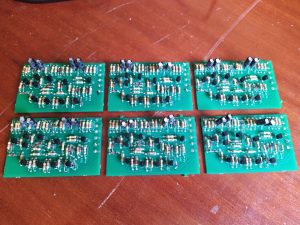

One large issue was around the printed circuit board (PCB) units, the central piece of hardware that acts as the brain for the rest of the unit. Wilson sourced these from South Africa and was surprised when he couldn’t find anything nearer, given the importance of PCBs in all technology these days. He provided all the schematic designs to the suppliers to ensure they were designed accordingly. He also decided that his team could learn to do all the soldering needed in-house, and so added this element to the training.

Another issue was getting the correct casing produced. When Wilson learnt of a casing supplier in Nairobi, fears that the casing would also have to be imported were allayed, but then seeing the lack of expertise by the only casing supplier, he had to become more involved. He still travels each time to supervise the casing production after a few failed attempts without his presence.

The final barrier to be overcome was the lithium ion batteries. The original plan was to purchase these locally but it soon became apparent that the price would be far too expensive. Wilson turned his focus to bringing in the raw material again, still from China, but instead got the female technicians to make their own batteries. This idea soon came to fruition and now the team is creating their own. This also led to further innovation, where now the battery is detachable and can be used as a market shop light or by individuals in the fishing industry.

Ultimately what makes this project noteworthy is how Wilson identified problems, and instantly came up with solutions. Whilst his expertise focused more on the product itself, there was constant feedback and suggestions from his team. This all stemmed from the mindset that “the team can do this, in-house and better, we just need the tools and the expertise”.

Innovating towards financial sustainability

With both the social and technological solutions in place and scaling, Wilson has started to shift his attention to how he can take his venture to the next level. The products completed a testing process at the University of Nairobi Lighting Laboratories, and with these results the team is now ready to move forward in improving the product according to the final testing report the team received.

Innovation is what drove this project forward, testing hypotheses and applying continuous learning and improvement. The team wants to succeed and be market ready, and the potential if they get it right is enormous. With 28.6 percent of the population in Kenya without electricity (World Bank 2020), the market is there to have a prosperous and impactful company.

The project is now looking for further investors or financial support, so they can continue this success story. The finances would be spent on employing the team of female engineers to continue and grow production. It would also be invested in cutting edge equipment that is currently not available or rare in the region.

Beyond this, Wilson has a larger vision. He has been developing a partnership with Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology and the University of Nairobi to ensure the students of electrical and electronical engineering have access to the practical elements whilst studying. His dream is to build a regional research and development institution where students can gain practical experience whilst providing research opportunities in the field of sustainable and green technology.

To learn more about this project, check out the visual presentation below:

Photo details:

1. Testing SolarE, the PicoSolar system (Photo Credit: Wilson Okwako)

2. Preparing the printed circuit boards (Photo Credit: Wilson Okwako)

3. SolarE, the final product in different colors (Photo Credit: Wilson Okwako)