To bridge the gender gaps throughout the energy supply chain and in decision-making groups, ENERGIA, EnDev, Modern Energy Cooking Services (MECS), Hivos and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) launched the Gender and Energy Innovation Facility (GEIF) in July 2020.

The Facility supported pilot projects in Kenya, Tanzania and Nepal that developed, tested and evaluated innovative approaches to address the persistent gender energy challenges in three thematic areas:

i) gender and energy entrepreneurship and employment,

ii) gender and energy in the care economy, and

iii) gender in energy policy and practice.

Over the course of about two years, the Facility oversaw 43 applications, 28 boot camp innovations, 10 first-phase projects and 6 scale-up projects.

According to the GEIF main focuses, the Facility supported innovation projects that pushed for government engagement to change policy or invest more in clean energy; developing new products or services that were linked to clean or cleaner energy; increasing awareness of clean energy products; increasing accessibility to clean energy products; empowering women through upskilling and breaking gender norms for the benefit of women.

Some great examples of gender and energy innovation projects are the Jiko Point project from Tanzania and the female-led one-stop clean cooking shops in Nepal. Nukta team, through their Jiko Point project, used digital technology to introduce new concepts such as boys cooking school and anonymising gender when publishing, thus experimenting with changing the position of especially young women in the process of adopting modern ways of cooking. The “Women Network for Energy and Environment (WoNEE)” in Nepal trained two cohorts of women who owned or worked in electrical appliance shops, on how to maintain and repair e-cooking stoves. A few months into the program, these women became advocates of clean cooking, sellers of e-stoves and technicians able to repair their goods.

Dealing with Change

Kicking off a Facility with participants from multiple countries is never easy, and doing this during a global pandemic, and ending as the world enters a financial and energy crisis, meant many changes throughout.

To start with, the boot camp, which was originally intended to be in-person, was shifted to being online, which provided new challenges in terms of access to the internet and then internet stability. Through a combination of less intensive applications like WhatsApp, providing the opportunity to film pitches and shortening the boot camp, teams were able to get fully involved in and benefit from the boot camp, which had seemed improbable if not impossible at the very beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, hosting the boot camp and the mentorship online limited bonding opportunities between projects and with those running the GEIF.

The experience with the GEIF suggests that, whenever feasible, in-person elements contribute to strengthening trust, rapport and outcomes.

Meeting New Players

The Facility drew interest from organisations with established expertise in its target fields. A number of them brought similar ideas from before, whilst others were really looking to add to their existing repertoire in an innovative way. At the same time, it was also able to attract some individuals or organisations who had not been part of such a process before. They shared skills or expertise from other sectors (for instance advocacy, paper production, worm culture etc.), while adding impact on gender and energy.

The learning curve was quite large for them, as they had to get to grips with project management practices of donor-funded initiatives, which they were often not used to. In such cases, the mentors’ and project managers’ support had to be quite flexible and open to the specific needs of each team, with significant communication, innovation and pivoting happening on the side of the program coordination and support as well.

Market Awareness

With innovation being a key part of the Facility, there was a stark difference between those projects who had carried out their market research and those who had not. Some claimed certain products or services didn’t already exist, when in fact there were a number of players in the sector already; whilst others truly brought innovative ideas to the table.

These differences presented additional challenges in the process of selection where expertise in specific fields, as well as familiarity with the local context and research, was crucial in order to weed out the truly innovative proposals. Through flexibility and advice during the boot camp, the GEIF enhanced and pushed the innovative elements further and worked with mentors on researching the local market and creating business models, which were consolidated throughout the mentoring stage, where teams were really pushed to think outside of the box.

Checking the Privilege

Crises, whether about health or the economy, always further deepen the existing divide impacting the most those who are already underprivileged. The same was true for implementing programs in the COVID-19 pandemic. As COVID-19 vaccines were first delivered to first-world countries and lastly to countries such as Kenya, Tanzania and Nepal the global injustice became even more visible. Tailoring the program implementation to the pandemic and to the existing cultural and economic differences, raised , more than ever, the level of awareness of own privilege as well as a new owe of the bravery and determination of the teams working in such circumstances.

Even more so, privilege must be considered when programming support for innovation. Innovating means taking a risk and the process of experimentation must include failure as a viable option. If failure is not a viable option it means that the answers are already known and there is no room for experimentation, and thus there is no innovation. As much as this is a well-known fact to anyone dealing with innovation, the cost of risk according to privilege is less considered. As the social innovation wave started in the Anglo-Saxon culture and spread through the Western hemisphere, not a lot has yet been explored and considered about the cost of risk for the underprivileged individuals or communities. Thus, good assurance was made for being especially sensitive and considerate of the fact that testing an innovative idea includes raising hope among those in need and underprivileged communities. Failing, if the hypothesis is disproved, even though potentially foreseen and even taken into account by the Program, carries a high cost for those working in difficult contexts.

The Spectrum of Innovation

Whilst innovation does not necessarily mean something completely new, it still infers a distinct change in the way something is or has been done. Many teams at the boot camp came along with similar projects with soft changes. Therefore, the boot camp was utilised as a place to encourage all teams to stretch and plan for true innovation.

At the same time, the nature of the proposed innovations differed significantly . Most commonly, innovation as positioning was proposed, meaning proposing to test something already existing in a new context and arguing that the contextual change is large enough or important enough to require retesting of the original solution in a new context. For example, even though training women to work with electronic equipment might not be innovative, doing that in a specific location for a specific product and by teaching a skill-set dominated by men is an innovation by positioning an existing solution (training) in a new context. On top of positioning, product and process innovations were a part of the Facility, with new types of locally produced pico solar batteries, cook stoves, briquettes, paper production, and solar or solar-powered cook facilities being innovated.

Main achievements

The “Gender and Energy Innovation Facility” truly designed a new approach to supporting innovation. The approach to ensuring an expert Program was three-fold:

- The Facility developed an expert Innovation Agenda with a clear definition and operationalisation of what innovation includes. This enabled guidance through all the phases of innovation selection as well as expert mentorship support during the experimentation (implementation) phase. In short, the Facility, from the start, knew what it was looking for and supported it.

- Secondly, the Facility offered training (during the boot camp) in the field of how to experiment with innovation hypotheses and how to learn from the experiment. This additional training significantly improved the original proposals and provided a process in which a much more informed decision about the team’s potential to innovate could be made.

- Finally, the Facility offered innovation and expert mentoring support throughout the innovation implementation process. This provided the teams with support and guidance as well as that additional expertise that they might be missing in their teams. This was especially valuable for the younger and more inexperienced innovators.

Last but not least, the Facility excelled at two crucial technical aspects:

- Providing unwavering financial and technical support throughout the two years, in the face of the pandemic. In a situation where a lot of programs were cancelled or postponed, the Facility always managed to find motivation, staff and resources to push through, to provide consistent service to its users. The motivation and the dedication were indeed tested and proven steadfast in the face of challenge.

- In a complementary but quite opposite way, the Facility showed flexibility and openness to learning and developing its approach to support innovation. Engaging experts and finding new ways to select, train and support the teams, it provided bespoke unique support to each team according to their needs and goals.

Lessons Learnt

As with any program, and especially one demanding as supporting innovation, there were several unforeseen needs that were not planned from the beginning but emerged during the implementation of the Program.

For most of the duration of the Facility, a whole set of new tools was developed. For example, in order to track progress and mentorship support, the Facility developed a real-time online mentorship tracker. The series of tools that were developed during the implementation of the Facility were organised and presented in the GEIF Tool Kit in order to be shared with other program developers. There is a whole wealth of tools that the Facility staff and experts were able to develop during the implementation of the Program in order to meet arising, unforeseen needs. Based on some challenges that were recognized among beneficiaries when it comes to knowledge about innovation and community resistance to change, an innovation tracker has been generated, in order to track how the experiment proceeded as well as to be able to share with others what advances have been tested and made in a certain field.

A Peek Behind the Scenes

In the process of mentoring innovation, synergies were sought between the expertise of the teams working on the ground and the expertise of their mentors, in order to ensure not just the originality of the innovations but the originality and improvement of the methods used in reaching the goals set by the teams. One such example is the process that took place after the training of young women, and school drop-outs, for electrical (solar) technicians by the organisation TAREA in Tanzania. After the initial training, a new phase began, where women were trained on the job. In ensuring that gender equality was a core priority, the issue of hiring women mentors soon arose. There the team faced one first obstacle. When innovative things are done, too often tools, processes, skills and personnel for their implementation do not exist. Therefore, there were no senior women technicians who could train the young women that were a part of the program. The team reported the problem to their mentor and had no choice but to employ men to train the young women as technicians. In several following mentorship sessions, they analysed whether the problem was that men were training women or that women were being introduced to and provided with power (in the form of knowledge and skills) in a traditionally male-dominated field (that of energy and electronic equipment). The real issue turned out to be ensuring the transfer of power from men to women. The mentor suggested existing literature on the topic and provided recommendations on what to avoid and what to ensure in this process. As a result, the following Guidelines for Men Mentoring Women were developed.

Guidelines for Men Mentoring Women

An example of “process innovation”

Most societies are patriarchal societies where shifting power in professional life, and especially in certain male-dominated fields such as energy, needs to happen. Keeping knowledge and skills within one, dominant group is very often a clear way of keeping power within that group. Thus, transferring knowledge and skills in a traditionally male-dominated sector will very likely include transferring knowledge and skills from men to women. Although that can be avoided by finding women experts and engineers and specifically choosing them to mentor and teach, this might not always be possible nor impactful as being a woman does not necessarily guarantee sensitivity to traditional gender roles and issues of inequality that comes with it.

Transferring knowledge and skills from men to women in the field of energy became a horizontal issue in supporting GEIF social innovation. In order to tackle any issues in that process, the book “Athena Rising: How and Why Men Should Mentor Women” by W. Brad Johnson and David G. Smith (2016) was provided to the TAREA-led GEIF project in Tanzania in order to share and discuss research in this area and to create specific Guidelines for men mentoring women.

A “how to” guide for male mentors was co-created and is available hereafter.

- “It is not the same” – the gender bias

Too often, men do not even realise that the way they experience the world, work, competition, and ambition is not the way others (namely women) experience it because this world was tailor-made for men, by men. Thus before males start mentoring women, as a man in the field of energy, he should take a bit of time to think about assuming mentees’ process or that experiences are the same. Research shows that women have been socialised to hesitate to ask for what they want, avoid appearing too confident, avoid conflict (thus not speaking up or challenging rude or sexist comments), work to please, deny discomfort or anger, choose between being attractive and being smart, and always cooperate and never compete. - Be prepared

Before the mentoring process, it is good to have a reflection on how gender roles are seen by the mentor and mentees. Because there is a clear message on what women should or shouldn’t do and what men should or shouldn’t do, how they should act in society. - How are men and women seen as professionals?

The good questions to be asked in this process is how women are seen and what roles and jobs are assigned to them, and how that differs from the male role and why it differs. - How is the process of men mentoring/teaching women seen?

While it is straightforward to fall into a gender script where complimenting a woman on how she looks reaffirms her as a woman, this is entirely unacceptable from a mentor. Making mentee feel good can not involve traditional gender affirmations that reduce women to having a role in the world that is being attractive to men or being nurturers/mothers. - Establish the context of trust – nobody is perfect but there is a need for honesty

Naming and honestly speaking about prejudice or sexism can make for more trust in a professional relationship. It is important to bring up these issues. B eing honest about having even conflicting emotions, for example at the same time wanting the field of energy become a space of equal opportunity for men and women as well as having insecurities if that is possible, will enable more trust between mentor and mentee. - Do not assume – ask

Assumptions about mentee’s needs and feelings are not welcome in this process. Historically women have been taught to be silent and to put others’ needs first so it might be difficult to verbalise and be comfortable with speaking about what she wants or needs. Thus, make it into an exercise of writing down the rules of the mentorship process. It is good to ask a mentee: what do you need? How would you like me to teach? What makes you feel comfortable, what worries you etc? - Tell them and show them they belong

Early on in people’s professional life, people can feel like imposters and need confirmation, support, and encouragement from someone they admire, look up to and consider a professional that they belong to. This is especially hard for women in these sectors, where they might feel that there is no place for women or that they do not belong. A mentor should ensure some extra time and support for a mentee and let her know there is a place for her in the field and that she belongs. - Taking credit and making mistakes

Research shows that women are less likely to take credit for their professional achievements. Unlike men, they will attribute their achievements to someone else, luck or the team. Make sure, as a mentor, that you ask your mentee to talk about her achievements and encourage her to speak about what she has done well. Try and encourage her not to just agree when you mention she has done something well but to start every session by saying what she has done well, or her achievement in order to get comfortable with taking credit. Normalise mistakes as a learning process by talking freely about mistakes and how people got past them.

Conclusions

As with any endeavour, there are always needs that are unforeseen but that cannot be met or examined during the process of Program implementation itself. At the same time, working with ten teams, especially in their scaling phases, reinforced the need to keep supporting and funding innovation as it has a greater potential for change than repeating known solutions and much less funding is available compared to existing, tested solutions..

One of the main takeaways from implementing such a diverse spectrum of innovation experiments is that budgeting and activities plans and processes should be flexible enough to accommodate various types of innovation experiments. Building infrastructure or a new product requires a different approach and support than changing a process or policy advocacy.

Choosing the right and truly innovative ideas to support as well as to scale in a second phase remains a difficult task in any program that supports innovation. What an individual or an organisation considers innovative is often very context-dependent and may stem from being unaware of other experiments or a cognitive bias related to their own ideas. Dedicated work needs to be put into fact-checking experts that evaluate the true innovativeness of an idea that needs to undergo a phase of objective fact-checking process. Additionally, a set of criteria for evaluating the scale potential of innovation that includes the innovativeness of the final solution, the potential of the innovation to create impact (qualitative impact) and the adaptability of innovation (the interest to adopt it, or produce it etc) (quantitative impact) should be defined and tested.

There is still a lot to find out and develop in the complex relationship between evaluating innovation and impact in programs such as this. An important conclusion is to design innovation and impact indicators and measuring strategy that can be applied, and collected, throughout the Program implementation as well as analysed at its end. Understanding how to track and evaluate innovation (which must include failure) and impact (which must include success) remains an important and challenging task for the future.

Photo details:

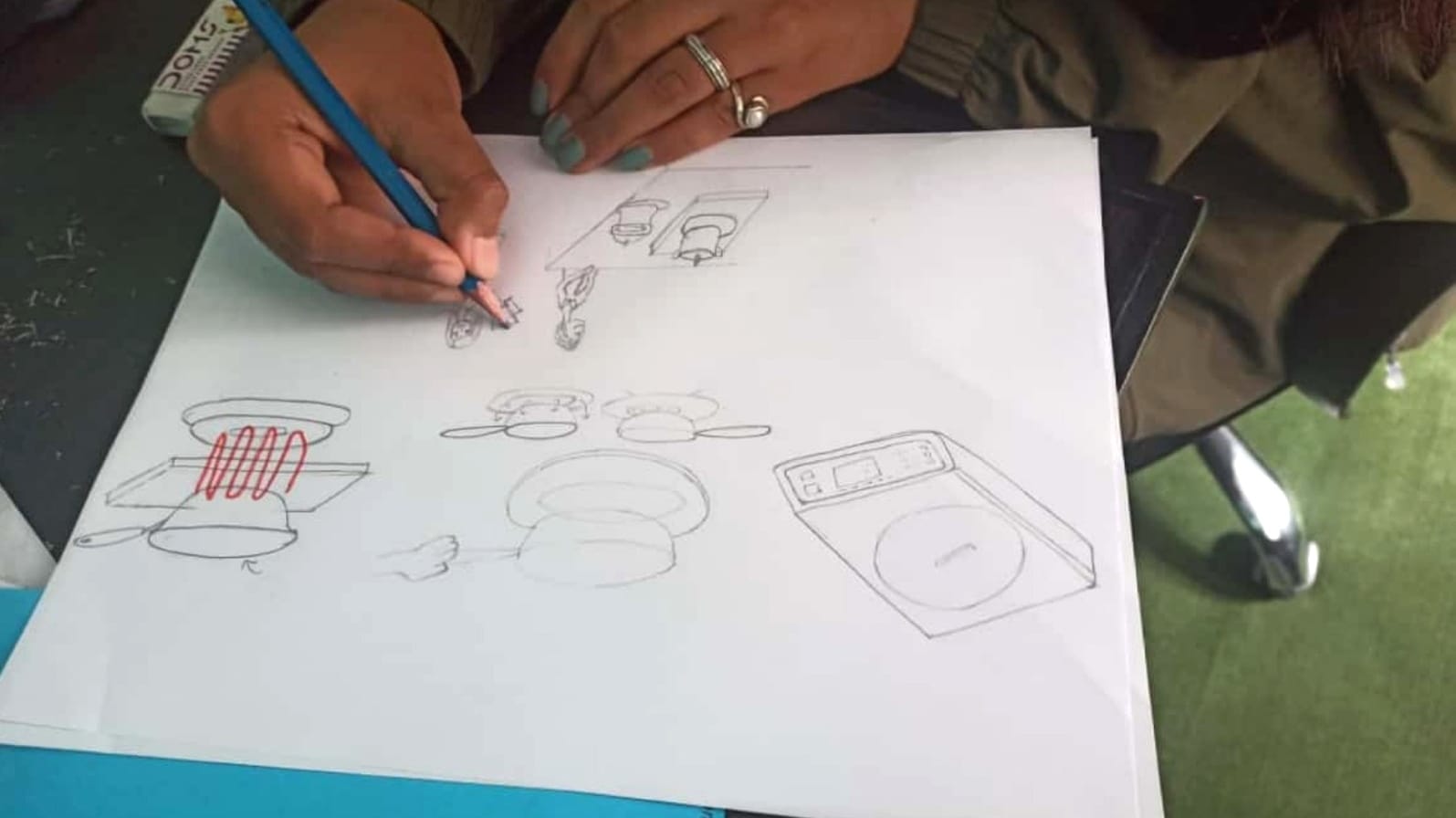

1. Bootcamp in Nepal. A woman draws the utopia of her innovation. (Photo credit: Swasti Aryal)

2. A utopia of sustainable women oriented paper production innovation in Nepal (Photo credit: Durga Bahadur Karanji)

3. Working on the PicoSolar system (Photo Credit: Wilson Okwako)